“Here is my hand, here is my touch, an unction of my heart to anoint your restless soul……”

“Here is my hand, here is my touch, an unction of my heart to anoint your restless soul……”

In today’s society oil has become an issue of pollution; we have abused this sacred blood of the earth and now reap all the calamities that follow such ignorance. Tagore speaks in Hindu terms of the anointing of a new King, he refers to the oil as being a preparation for sacred duties and every drop of this fragrant oil relates to every drop of the kings duties and the mundane ones he must now let go. Tagore speaks of flouting that oil by extravagant use or by ignoring the duties. He is quite clear that this is a direct invitation to the demons that wait for such ignorance and abdication of the sacred.

Anointing is here defined as a making and marking of the sacred, as well as an invitation for that which is ‘royal’ (divine’ to come and dwell within the anointed ‘house’. “Prepare, prepare, the King is coming, I have anointed the lintels and doorways, surely he will enter within.”

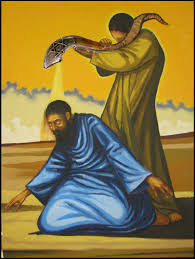

The ancient ones knew and used anointing as a setting apart of the sacred, the royal, no matter what external was presented. David was a humble scruffy shepherd boy, along comes the prophet Samuel. Samuel sees what none else can see, including the shepherd dudes hanging with David. Samuel takes olive oil and pours it on the head of David. Almost immediately everyone one of the shepherd gang see David differently, and fall down and acknowledge him as King. It is only now that Samuel reaches out an embraces David as if some greater Divine love is being manifested. I often wondered if this was because Samuel saw more than the moment in front of him.

The ancient ones knew and used anointing as a setting apart of the sacred, the royal, no matter what external was presented. David was a humble scruffy shepherd boy, along comes the prophet Samuel. Samuel sees what none else can see, including the shepherd dudes hanging with David. Samuel takes olive oil and pours it on the head of David. Almost immediately everyone one of the shepherd gang see David differently, and fall down and acknowledge him as King. It is only now that Samuel reaches out an embraces David as if some greater Divine love is being manifested. I often wondered if this was because Samuel saw more than the moment in front of him.

There is an old thought that olive oil only comes from the fruit if it is pressed with extreme pressure and weight, almost as if the olive has to be destroyed in some suffering to give up this sacred essence. For the ancients Olive Oil was the oil of sacrifice and as such it marked the great transitions of catharsis and penance. Gladiators were ‘oiled’ before going to their death, the sacrificial victims of the Babylonian gods were daubed with olive oil and the heroes who took katabatic quests were oiled before after. Strange we simply pour it on our salads without a thought of how and why it gets to the table.

Andrew Harvey in his book ‘The Way of Passion: a celebration of Rumi’, says,

“Those anointed with kohl are the ones who have established a passionate relationship between lover and beloved; God himself comes down and anoints them with vision that hey can see the true nature of reality. For the anointed one who is awake, the fire of death, the fire of the mystic becomes the supreme experience of love, and that all that was terrible and horrible is revealed as a rose garden and the true face of love.”

Harvey takes the essence of anointing deeper with the act not just of setting one apart, rather placing them in direct relationship with the divine and by which ne awareness, insight and vision are acquired almost as default. And yet given our journey through these words that default comes at a price; sacrifice, duty, devotion and the fervor of passionate and love.

Reference to this love can also be found in The Gospel of Philip, which is contained in the Nag Hammadi Library: ‘Spiritual love is wine and fragrance. All those who anoint themselves with it take pleasure in it. While those who are anointed are present, those nearby also profit (from the fragrance).

Rooted in the concept of this sacred act is passion, fervor almost an extreme and excessive intimacy with the other that overrides social taboo and accepted etiquette, as if the act of anointing reaches directly into the heart, overriding the mind and exploding in such devotional intimacy that those around without hesitation falls into some otherworldly ecstasy.

The classic example of this would be the anointing of Jesus by Mary of Magdela, who demonstrated unabashed devotion. When rebuked, Jesus himself, replies, “She prepares me for my burial.” Most take this to mean a prophecy of his death, yet some suggest that he was talking about being separated from the mundane concept of love and talking of a deeper immersion. It is not long after this that he washes the feet of his followers in the same immersion of burial into a new consciousness.

The classic example of this would be the anointing of Jesus by Mary of Magdela, who demonstrated unabashed devotion. When rebuked, Jesus himself, replies, “She prepares me for my burial.” Most take this to mean a prophecy of his death, yet some suggest that he was talking about being separated from the mundane concept of love and talking of a deeper immersion. It is not long after this that he washes the feet of his followers in the same immersion of burial into a new consciousness.

The act of anointing is a prayerful immersion into that unknown quality of love, almost as if we know in our hearts of the essence of love, yet cannot define it though the words of our mind. We surrender to our bodies and its sensuality as the only recourse to be prayer in action. Anointing becomes a calling to change, to separate from the absence of love, from the isolation of dis-ease. Anointing in its truest sense is healing, to be gathered and made whole.

“They drove out many demons and anointed many sick people with oil and healed them.” Mark 6:13

This anointing was a call to those already, as Harvey suggests earlier, anointed…

“Is any among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil.” James 5:14

That love is a state of being and within that state these ‘anointed’ may embrace others into that state. There for anointing becomes a rippling outwards affect, a passionate fervor that cannot be bound or stopped once the oil is poured.

The sensuality of oil cannot be denied and yet to anoint is to daub, smear, caress with the ‘fragrance of devotion’. There is now exact definition of ‘fragrance of devotion’, save an act of love that is noticed. Substances used for anointing vary across traditions, a variety of oils, especially those prized and valued, milk, butter, yogurt, mud, blood, water amongst many. These ‘fragrances’ were defined as valuable according to scarcity or religious metaphor within their own traditional setting. Milk products are valued as the maternal essence of the cow, the sacred mother in Hinduism and indeed in the Sagh’ic Tradition. Mary’s costly ointment was Nard a name for emulsified spikenard, a rare and expensive oil that requires much labour and trial to prepare and as such was only used in the anointing of kings, prophets and priests, this meaning was not lost on her anointing of Jesus.

The prayer of anointing, that of honouring a new way, a new life, a separating from an old state of being, is not only confined to the higher rituals of ordination and the like. Within the Sagh’ic Tradition every new born is anointed with milk and water and to maintain the cycle of life into death into life, the dead are anointed with milk and water.

Warriors are anointed with the oil of the holly to honour their bravery, and this ‘warrior bravery’ is defined as any who enter into battle or quest and defeat that which keeps them or others from love. In the Sagh’ic every de-possession, every soul intervention is blessed with an anointing. Brides and grooms are anointed with the ‘green’ of the forest.

Warriors are anointed with the oil of the holly to honour their bravery, and this ‘warrior bravery’ is defined as any who enter into battle or quest and defeat that which keeps them or others from love. In the Sagh’ic every de-possession, every soul intervention is blessed with an anointing. Brides and grooms are anointed with the ‘green’ of the forest.

Probably the most spectacular Sagh’ic anointing is that of Flanndearg, a scarlet powder used to mark the skin in Fire Rituals, Warrior Rituals and to embalm the bodies of the dead. In ritual sof the dead it is Ungadh-Bàis, an embalming ointment to separate the dead from the living as the newborn child arrives covered, anointed in its mothers blood to separate it from the otherworld, this anointing reverses the original ritual of separation.

To anoint is to both separate as something new and sacred, and to heal in gathering to the one and whole. Anointing is not something that one does to another, or something done to us by another, it is a interactive sacrament of being love.

“Here is my hand, here is my touch, an unction of my heart to anoint your restless soul that my soul may know peace.”